ISC receives a variety of court orders for many different types of transactions, such as mortgage proceedings, vesting orders, orders correcting titles, orders under

The Family Property Act, and federal restraint orders under the

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

We encourage lawyers to send their draft orders to ISC for review to ensure that the orders meet our requirements and can be acted upon by the Registrar. It is much easier to amend a draft order than to have to go back to the court once an order has been granted. The Business Services Department of ISC has a number of lawyers that are willing to review any draft orders before they are provided to the court.

Direction to Registrar of Titles Required

When submitting a court order to ISC to act as authorization, the proper wording for the order is to direct the Registrar of Titles to do whatever it is that you are attempting to do (i.e. accept an application to transfer a title or discharge an interest).

Historically, for a court order to be effective it had to be directed to the Registrar of Titles. In

Re Transfer of Part of Block 7 Buchanan Townsite and Heier, [1949] 2 W.W.R. 174 (Sask. K.B.), Thomson J. stated at p. 177: “Under sec. 202 of

The Land Titles Act orders of the court must be obeyed by the registrar of the land titles office when directed to him.”

This confirmed prior decisions by the Master of Titles in

Hudson’s Bay v. Goodwin (1915), 8 W.W.R. 1339 that an order must be directed to the Registrar by name or contain a clear direction to the Registrar to do something or be intended for the Registrar’s action by clear implication. In

Avelsgaard’s Case, [1918] 2 W.W.R. 946, Master of Titles Milligan held that the Registrar was acting within his authority in rejecting an order not directed to him.

While a court order should contain a direction to the Registrar, the preferred wording is not to direct the Registrar to transfer the title, but rather to direct the Registrar to accept an application to transfer the title. This is because of the wording contained in Section 109 of

The Land Titles Act, 2000:

109(1) In any proceeding pursuant to this Part, the court may make any order the court considers appropriate, and in so doing may direct the Registrar to, or authorize any person to apply to the Registrar to:

(a) register, discharge, amend, postpone or assign an interest; or

(b) transfer title or make changes to a title.

[. . .]

(3) On an application to the court pursuant to this Part, if the judge hearing the application considers it appropriate to do so, the judge may make an order:

(a) directing that a title be vested in any person; and

(b) either:

(i) directing the Registrar to transfer title or to make changes to a title;

or

(ii) authorizing any person to apply to the Registrar to transfer title or to have changes made to a title.

An example of an order that contains this type of wording is as follows:

1. The interests in relation to Interest Register No. 999999999 on Title No. 888888888 vest from ________ to ______________;

2. The applicant is authorized to apply to the Registrar of Titles to assign the above interest, to effect a change in the interest holder in the Land Registry from ________ to ____________ and direct that the Registrar of Titles accept this Court Order as the authorization for such applications.

SJR/PPR Orders

We received an order for the discharge of a writ that contained the following wording:

The judgment and writ of execution issued the 17th day of July, 1998, against the Defendant in the within matter shall be set aside.

It would be better to have added the statement below to wording of this order:

The Registrar of Personal Property is hereby directed to accept an application to discharge the writ of execution registered as registration #111111111.

By quoting the registration number and directing the Registrar to discharge the writ, the person processing the request for discharge knows:

i) that the writ sought to be discharged is the correct writ and

ii) that the court has given the direction for ISC to discharge the writ, and is not merely directing the defendant to discharge it.

Foreclosure Orders

The most common errors made with foreclosure orders are:

- The usage of old world terminology like referring to the former land registration districts, the Master of Titles, directing the cancellation of the certificate of title and the discharge of encumbrance.

- The failure to specify which, if any, interests are carrying forward.

- The failure to use new world title numbers or parcel numbers.

ISC continues to receive foreclosure orders that use old world terminology, for example:

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED AND DECLARED that the Defendants and all persons claiming under them or any of them be and they and each of them are hereby absolutely foreclosed from all their and each of their right, title and interest in and to the following land:

Lot 1, Block 1, Plan 11

or

SW 1-1-1 W2

A better way to word the order would be to refer to new world title numbers or parcel numbers:

IT IS HEREBY ORDERED AND DECLARED that the Defendants and all persons claiming under them or any of them be and they and each of them are hereby absolutely foreclosed from all their and each of their right, title and interest in and to the following land:

Surface Parcel #111111111

Reference Land Description: Lot 1, Block 1, Plan No. 11, Ext 1 as described on certificate of title 99S11111, description 1

Title #222222222

We also receive orders that continue to state:

AND IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the Registrar of the Saskatoon Land Registration District do cancel the existing Certificate of Title to the said lands and do issue a new Certificate of Title in the name of the Plaintiff freed and discharged from all encumbrances save as hereinbefore provided.

This paragraph should not refer to the Registrar of the previous land registration districts, but rather to the Registrar of Titles or the Registrar of the Saskatchewan Land Titles Registry. This paragraph should also specify if there are any interests on title that carry forward. Also, the old world terminology ordering the canceling of title and referring to encumbrances should be replaced with the correct new world terminology referring to surrender of the title and interests rather than encumbrances:

AND IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the Registrar of Titles accept an application to set up a new Title in the name of the Plaintiff freed and discharged from all interests save as hereinbefore provided.

It is important that the court order specifies which interests are to remain on the new title. In the previous

Land Titles Act, an easement, a building restriction caveat, a true easement, a mortgage of easement, or a party wall agreement were not included under the rubric of “encumbrances.” In order to ensure the protection of third party’s interests if a court order came in indicating free and clear from all encumbrances, the policy was to continue the above interests on the new Certificate of Title unless the order specifically directed the Registrar to issue the Certificate of Title free and clear of such instruments.

Under

The Land Titles Act, 2000, the term encumbrance is not used. Nor is it defined. All interests are on the same footing, and are all defined as an interest; therefore, the previous distinction no longer exists. If a court order was submitted today indicating “free and clear of all encumbrances or interests”, no interests would carry forward, resulting in interests that should not be affected by the foreclosure possibly being removed.

Orders Preventing the Lapse of a Caveat or Builders’ Lien

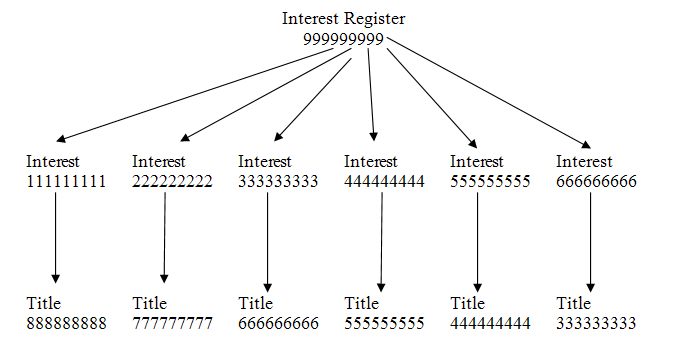

A common area of confusion with court orders preventing a builders’ lien or caveat from lapsing is the usage of interest register and interest numbers.

An interest register can contain more than one interest. For example, a caveat that was registered in the old world could have converted into more than one caveat that registered against more than one title in the new world. If your objective is to obtain a court order that prevents the discharge of all of the interests in the interest register, then it is appropriate for the court order to refer to the interest register. If the objective is only to prevent the discharge of one of the interests against one of the titles, then the court order should only refer to the specific interest number.

Here is an example of a problematic order:

The Registrar received a court order that referred to the title number and the interest register number. It said, “The caveat registered as Interest Register 999999999 against Title 111111111.” This was not correct, because the interest would be registered against the title at the interest level and not the interest register level.

For example, assume Interest Register 999999999 contains six interests, and the court only intended to prevent the discharge of two. Referring to the specific interest number rather than the interest register would avoid any ambiguity regarding what was to be locked. If the court intended to prevent the discharge of all six interests, then it would be appropriate to refer to the interest register number and not the interest number(s).

Using the picture that is above, if the Court intends only to prevent the lapse of two interests that are registered against Titles 888888888 and 777777777, then the order should reference the related interests 111111111 and 222222222. Discharging the interest register will have the effect of discharging the interest against all the titles.

Another court order the Registrar received referred to a “caveat registered as Interest Register 888888888 against Mineral Parcel 999999999.” Interest Register 888888888 contained 12 interests. Only two were registered against Parcel 999999999, and only one of those had a notice to lapse registered against it. Also, the court order referred to the mineral parcel registered in the name of X. It is the title in that parcel, and not the mineral parcel itself, that would be registered in the name of X. Even more problematic in this case was that there were two titles in Mineral Parcel 999999999, only one of which was held by X.

For clarity, the order should have directed the Registrar of Titles not to allow the discharge of Interest 777777777 as against Title 666666666 held by X.

Another problem regarding court orders preventing lapsing of caveats is that the wording of the order does not reflect the true intent of what the caveat holder wants. For example we received a court order that stated that a caveat was not to be lapsed for 30 days to give the caveat holder the opportunity to bring an action to protect the caveat. The caveat holder did begin an action within the 30 days, and then came to ISC to have the caveat locked permanently. The problem was the court order did not give ISC the authority to do this. Preferably, a court order to extend the time of a caveat should be done one of two ways:

1) Direct that the caveat be continued for a certain period of time to allow the caveator to bring an action, and that if such an action is brought, and a certificate of pending litigation is filed, that the caveat be continued until the action is disposed of.

This is the order that the client in the example above wanted to get, but the order was missing the second part that upon bringing the action and filing the certificate of pending litigation the caveat is locked and cannot be continued until the action is disposed.

2) Directing that the caveat be continued until further order or withdrawn by the caveator.

This order will result in the lock being put on, and not be removed unless a further court order is submitted or the caveator authorizes an application for discharge.

Certified Copy

We require a certified copy of every court order submitted to ISC. Rule 336 of the Queen’s Bench Rules of Court reads in part as follows:

Every judgment or decree entered and a copy of every order issued by the local registrar shall be filed; and a certified copy thereof under the seal of the court shall be received for all purposes as of the same force and effect as such original judgment, decree or order.

According to this section, a court order must contain the seal of the court to be considered a certified copy. The order must have the original signature of the local registrar, and not merely be stamped with the local registrar’s ink stamp. We will not be able to see the seal since it is embossed. However, we will know by the original signature of the local registrar that it is a certified copy. We do not require a certificate of notary or lawyer indicating that the seal is present on court orders. The requirement of providing a certified copy also applies to letters probate submitted for a transmission or as evidence for any other type of transaction.

Court Orders and Address

The position of the Land Registry is that the specific terms of a court order should be followed. If a court order provides a direction with a specific address, then the client number used on the application with that court order must contain the correct address.

An example of a court order containing a specific address was where the court ordered the title be issued to ABC Bank with a London, Ontario address. The client number submitted in the application was for ABC Bank with a Regina, Saskatchewan address. The application was rejected.